|

|

Back to 2018 Program and Abstracts

SPLENECTOMY DURING DISTAL PANCREATECTOMY: WHAT ARE WE REALLY DOING?

Laura Maggino*1,2, Giuseppe Malleo2, Claudio Bassi2, Charles Vollmer1

1Department of Surgery, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA; 2Unit of General and Pancreatic Surgery, Department of Surgery and Oncology, the Pancreas Institute, University of Verona Hospital Trust, Verona, Italy

Background. The performance of a splenectomy is one of the few major decision points in distal pancreatectomy (DP). Although this represents a particularly common clinical scenario, evidence regarding splenectomy and splenic preservation (SP) during DP is nebulous. The aim of this study was to analyze surgeons' opinions and preferred strategies regarding splenectomy during DP, and to identify possible contributors of variability in practice.

Methods. A survey assessing surgeons' beliefs and practices for splenectomy during DP was distributed worldwide, in 8 native-language translations, through 56 surgical societies (including the SSAT). The participants' answers were related to their self-reported demographic characteristics (age, region of practice), background (fellowship training, type of fellowship, scope of current practice), and indicators of experience (annual/career volume of DPs).

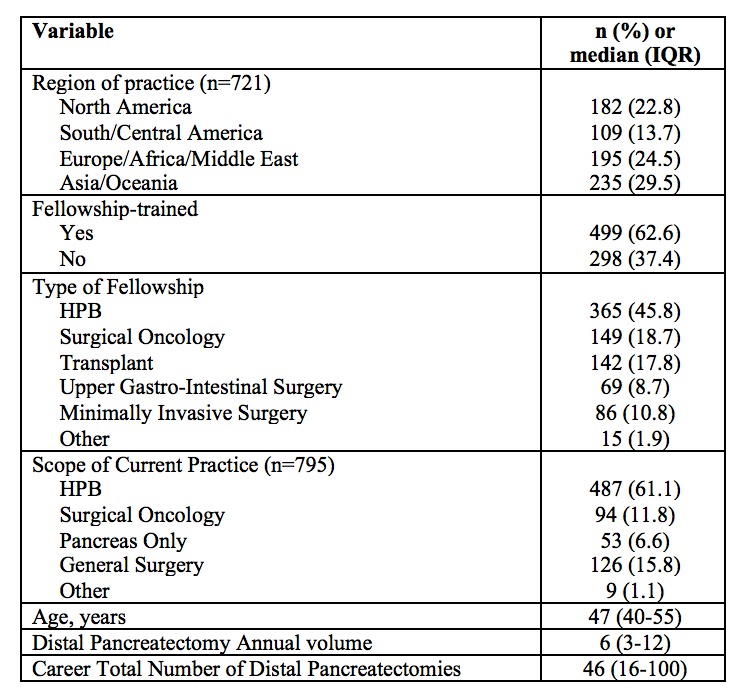

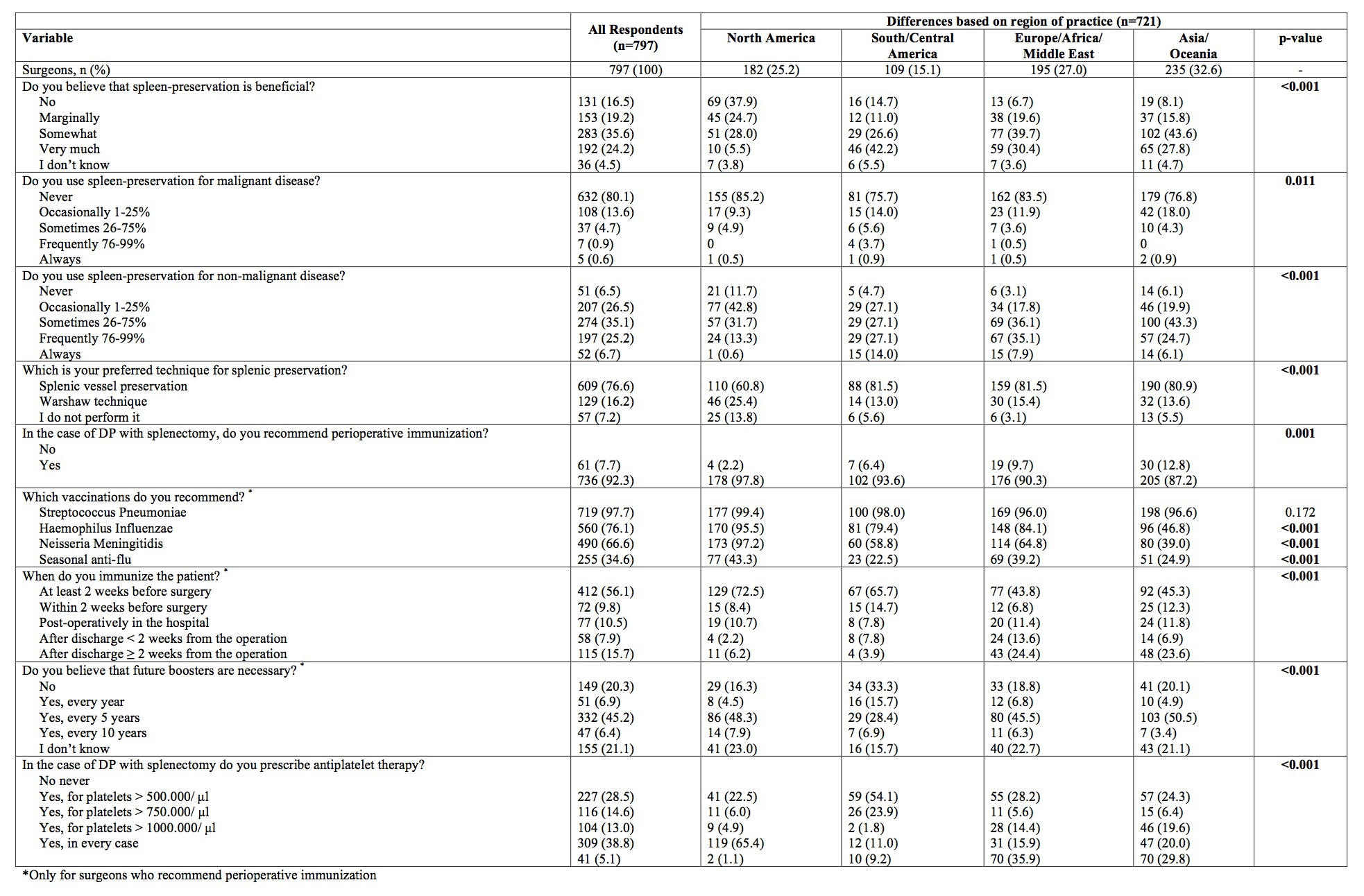

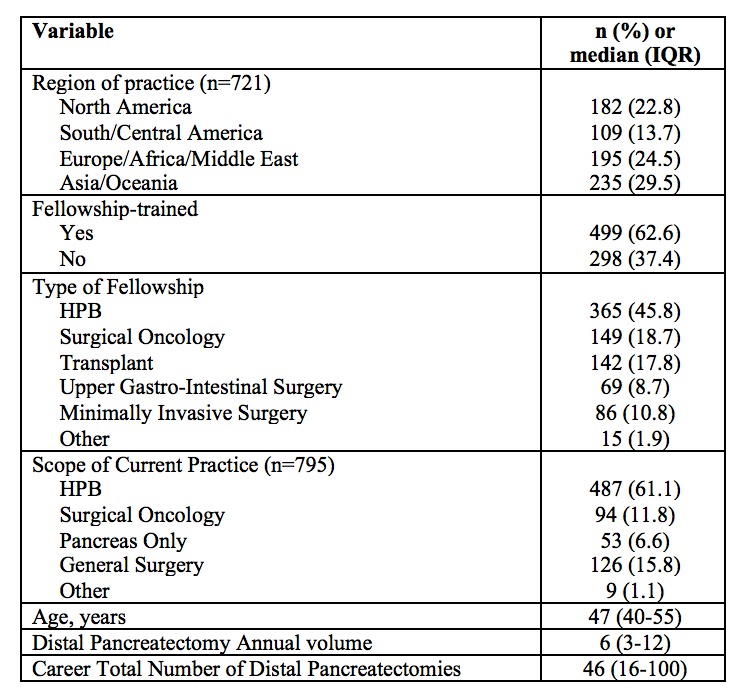

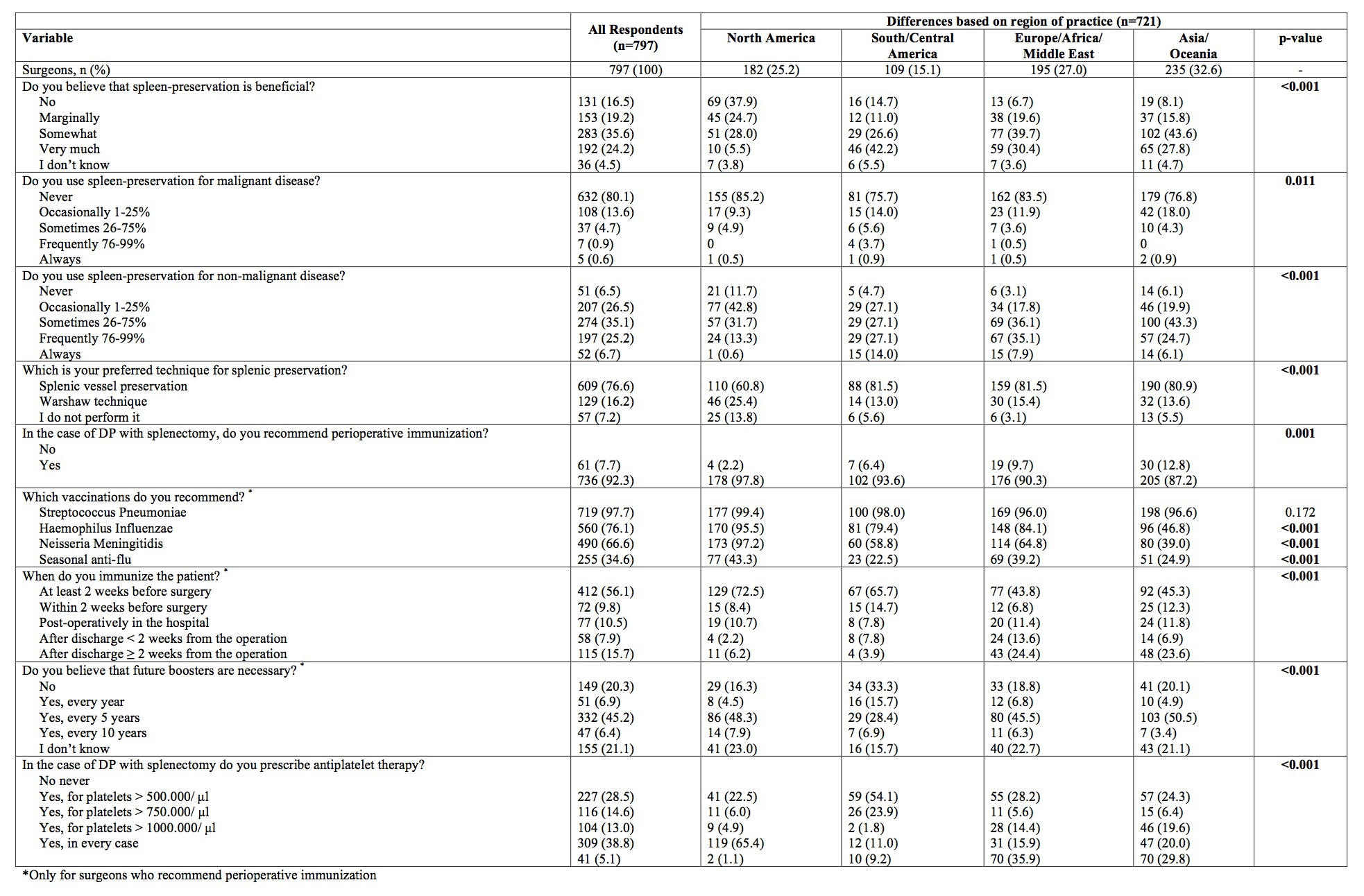

Results. The characteristics of the 797 surgeons, from 68 nations, are displayed in Table 1. Respondents are conflicted regarding the benefit of SP during DP, with 35% considering it not, or only marginally, beneficial. Conversely around 60% judge it to be moderately to markedly advantageous (Table 2). SP is rarely applied when operating for malignant pathology, while a wide variety of approaches are employed for managing non-malignant disease (Table 2). Among surgeons performing SP, conservation of the splenic vessels is by far the most common approach (82.5%), while the Warshaw technique is preferred only 17.5% of the time. In the case of DP with splenectomy, surgeons overwhelmingly agree on the need for perioperative immunization (92.3%). However, while S. Pneumoniae vaccination is almost always administered, those against H. Influenzae and N. Meningitidis are more rarely chosen (Table 2). Moreover, there appears to be a broad heterogeneity of behaviors regarding the preferred timing for immunization, with the most frequent being > 2weeks before surgery. Finally, there is no agreement on the need for anti-platelet therapy after splenectomy, and different cut-offs of platelets values are utilized (Table 2). Surgeons' opinions and strategies are to some extent related to their age, scope of practice, and indicators of experience, but the strongest driver of variability is geographic origin (Table 2). Conversely, fellowship training appears to have only marginal influence on practice.

Conclusion. There is wide heterogeneity in beliefs and practices regarding splenectomy during DP, which appears mainly influenced by the surgeon's region of practice. These results suggest that current behaviors are mostly driven by cultural factors and perpetuated dogmas, rather than scientific evidence, which remains largely inadequate. These findings indicate focused areas for further research and improvement.

Table 1. General characteristics of survey respondents (n=797)

Table 2. Surgeons' opinions and preferred strategies regarding splenectomy during distal pancreatectomy for all respondents (n=797) and stratified based on the region of practice (n=721 due to some surgeons not indicating their geographical area).

Back to 2018 Program and Abstracts

|