|

|

Back to 2015 Annual Meeting Program

Trainees and Operative Outcomes: the "July Effect"

Ammara a. Watkins*1, Lindsay a. Bliss1, Danielle Cameron2, Jennifer F. Tseng1, Tara S. Kent1

1Surgery, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA; 2Surgery, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA

Introduction: The impact of surgical trainees on patient care is increasingly scrutinized. The occurrence of mortality after major complications, also popularized as failure-to-rescue (FTR), has been proposed as a new outcome measure in large database series. Prior studies have been conflicted about the association of resident participation with FTR. Additionally studies have purported "July Effect," in which morbidity and mortality may be increased in the month of July when new house staff begin residency.This study aims to define the relationship of hospital teaching status, FTR and time of year in select gastrointestinal operations.

Methods: Admission diagnostic and procedure codes for pancreatectomy, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and colectomy were queried from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) during 2004 to 2011. Procedure month and urgency of admission were noted. Hospital characteristics including teaching status, bed size, location, and region were collected. Morbidity was established using secondary diagnosis codes. FTR was defined as mortality in a patient with at least one morbidity.

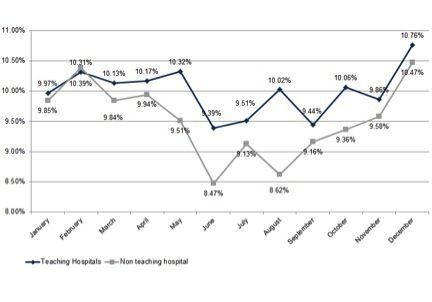

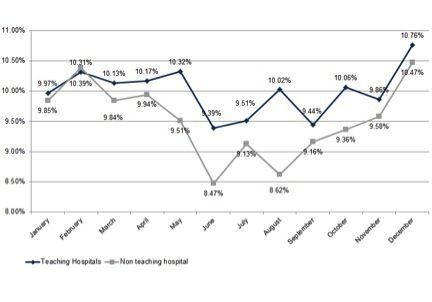

Results: 26,289 pancreatectomies, 567,369 laparoscopic cholecystectomies, and 512,510 colectomies were performed. Among them 21,567 (83.33%), 205,185 (46.2%), and 238,454 (46.69%) occurred at teaching institutions. FTR as defined occurred in 23,757 (2.15%) of all cases. Monthly analysis of FTR rates as an aggregate of these operations in teaching versus non-teaching hospitals revealed a statistically significant difference (p<0.001) predominantly between the months of May and August (Figure 1). In an adjusted, multivariate regression model of FTR, teaching status, urgency of admission, transfer from outside facility, year of resection, hospital bed size, hospital region, age, sex, ZIP code median income quartile, payer, and Elixhauser score were significantly predictive of FTR odds.

Conclusion: This study demonstrates that FTR at both teaching and non-teaching hospitals changed significantly by admission month. Overall, patients undergoing these select surgeries (as an aggregate) at non-teaching hospitals experienced lower rates of FTR compared to those treated at teaching hospitals. Additionally, there appears to be a larger difference in FTR rates from May to August. The concept of the "July effect" is supported by these findings. More studies to identify the causes of this increased risk of death following a postoperative complication and its temporal variation are needed to optimize patient outcomes.

Figure 1. Rate of death after complication (FTR) among patients with at least one complication in teaching versus non-teaching hospitals by admission month.

Back to 2015 Annual Meeting Program

|