|

|

Back to 2015 Annual Meeting Program

the Concept of Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma Is Still Valid? Analysis of Clinicopathological Features and Mutational Genes Profiling in a Series of 56 Cases.

Andrea Ruzzenente*1, Michele Simbolo2, Simone Conci1, Matteo Fassan2, Rita Teresa Lawlor2, Corrado Pedrazzani1, Paola Capelli2, Calogero Iacono1, Aldo Scarpa2, Alfredo Guglielmi1

1Department of Surgery - Division of General and Hepatobiliary Surgery, University of Verona Medical School, Verona, Italy; 2ARC-Net Centre for Appleied Research on Cancer and of Pathology and Diagnostics, University of Verona Medical School, Verona, Italy

Background and Aims: Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (PCC) includes two separate forms: those with a significant intrahepatic component, defined as intrahepatic perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (IH-PCC) and those without a significant liver mass which arise from the hilar extrahepatic large ducts defined as extrahepatic perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (EH-PCC). The aims of the study were to compare the clinicopathological features and mutational gene profiles of IH-PCC and EH-PCC.

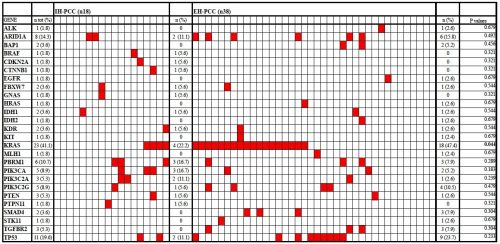

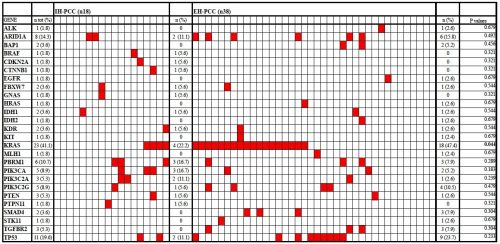

Methods: Fifty-six patients with PCC (18 IH-PCC and 38 EH-PCC), who underwent curative surgery in a single tertiary HPB surgery referral centre, were assessed for clinicopathological features and mutational profiling in 56 cancer-related genes.

Results: Mean tumor size of IH-PCC was higher than that of EH-PCC (5.2 cm ± 2.2 cm vs. 2.6 cm ± 1.5 cm, respectively, p < 0.001). No differences have been identified between the two subgroups in the rate of preoperative biliary drainage, major hepatectomies, caudate lobe resection and portal vein resection (p = 0.183, p = 0.614, p = 0.363 and p = 0.403, respectively). R0 resections were achieved in 83.3% of IH-PCC and in 60.5% of EH-PCC, p = 0.128. AJCC-UICC pT, pN and Stage were similar between the two subgroups (p = 0.101, p = 0.572 and p = 0.627, respectively). No differences have been identified in number of lymph nodes retrieved, in number of positive lymph nodes and in LNR, between the two groups (p = 0.448, p = 0.351 and p = 0.736, respectively). Median survival resulted similar between the IH-PCC and EH-PCC, respectively 20.1 months and 29.6 months, p = 0.241. At least one gene mutation was identified in 80.3% of cases (45/56). KRAS was the most frequent mutated gene, it was observed in 47.4% of EH-PCC but only in 22.2% of IH-PCC and the differences between the two groups was statistically significant (p = 0.044). In IH-PCC the other most frequently mutated genes were PBRM1 (16.7%), PIK3CA (16.7%), PIK3C2A (11.1%), TP53 (11.1%), ARID1A (11.1%). In EH-PHCC the other most frequently mutated genes were TP53 (23.7%), ARID1A (15.8%), PIK3C2G (10.5%). The mutation rate in these genes was not significantly different between IH-PCC and EH-PCC. Moreover the following genes BRAF, CDKN2A, CTNNB1, GNAS, PTPN11 were mutated only IH-PCC. Conversely, ALK, BAP1, EGFR, HRAS, IDH2, KIT, MLH1, SMAD4, STK11, TGFBR2 were mutated only in EH-PCC. (Figure 1)

Conclusion: Surgical treatment and prognosis are similar between IH-PCC and EH-PCC. Although our study analysed a limited number of patients, the mutational gene profiles differed between IH-PCC and EH-PCC suggesting differences in carcinogenesis. These abnormalities may represent potential target for directed, personalized treatment options.

Figure 1: Gene mutation profiling in the 56 PCC. Each column represent a patient, genes tested are listed in rows. Red rectangles indicate the mutations in a given gene and patient. The p values represent the statistical comparison in frequency of specific gene mutation between IH-PCC and EH-PCC.

Back to 2015 Annual Meeting Program

|